Shoot, Jump, Run: Abandoned by Human. Raised by Metroid.

(If you’d rather read this essay on your Kindle, you can do so by clicking over to the Kindle store right now)

(If you’d rather read this essay on your Kindle, you can do so by clicking over to the Kindle store right now)

Shoot. Jump. Run. Samus Aran and I, we both came into existence this way.

For video game creator Yoshio Sakamoto, those three verbs described all he knew about the project he was told to create, a game that would become 1986’s Nintendo classic Metroid, a game that would seed a cherished series and inspire an entire video game genre. Sakamoto handled the responsibility of those verbs with dignity.

My father—never one to care about the gratification of others nor one to welcome responsibility—handled the experience of creating me with the same verbs, though in a different context: shoot (impregnate), jump (get dressed), run (leave).

Samus and I, we might as well be siblings, right?

![]()

My father had a problem with cocaine. This I conclude based on a mashup of my own vague memories of white powder, cosmetic mirrors, and razor blades[1]Believe me, I know how much this sounds like b-movie set dressing and therefore simply cannot be real. But I assure you, these tropes are real., paired with my mother’s slipped anecdotes during passive aggressive asides when it became too much for her to maintain composure in front of her children. She’s a saint. Never one to talk bad about my father in front of me, but even a saint will eventually buckle as time without child support payments stops being measured in months and turns instead to years and then to decades.

Much like Sakamoto, though, my father made the most of his limited toolset. Where Sakamoto had three simple verbs, my father had two enormous holes. See, my father was born with the infamous “Ross nose,” which is identified by nostrils big enough to store an 8-ball inside (the pool kind and the drug kind, probably simultaneously). The way I see it, considering the awe-inspiring size of this genetic abnormality he was obligated to stick something in there, and if not hotdogs for the sake of winning a contest (that should exist, if it doesn’t) why not cocaine? Tall people play basketball. Smart people cure disease. Tepidly accepting fathers with holes the size of military battle wounds on their faces snort things.

My parents divorced when I was five years old, so the implied speed of my origin story—impregnate, get dressed, leave—may be unfair. Perhaps more accurately the sequence is as follows: cum, do some cocaine, smoke, react to cocaine in post-cocainey ways, join the Navy, move family to Alaska, be disappointed that the “white powder” advertised in the Alaska tourism pamphlet referred to snow, find drug dealer in Alaska who sells “other white powder,” do some other white powder, impregnate wife with third child, leave.

Such domestic specificity and weight would not have worked for a video game plot in the mid-80s[2]We as a culture didn’t yet have the ethical flexibility to render domestic malfeasance in 8-bit graphics. That wouldn’t be popular until the 1988 port of Double Dragon when kids the world over … Continue reading. Story was often relegated to single screens of text (The Legend of Zelda) or a montage of melodramatic images (Blaster Master). Keep in mind, at this time video games hadn’t yet found the proper domiciliary categorization. Were they toys? Sometimes. Were they family entertainment? Sometimes. Were they simply a cash grab for overzealous profiteer game makers and therefore on the verge of being ignored by the North American consumer entirely, to be forgotten as just a fad? Yes. But we’re getting ahead of ourselves.

Technical limitations, I believe, actually helped keep video games in the consumer’s good graces. Simple presentation, simple interface, simple story, simple mechanics, all these things promoted the idea that video games were for kids and the idea that they were anything more was simply incomprehensible. The Entertainment Software Rating Board, the American self-regulatory organization that assigns age and content ratings to consumer video games, was still eight years from existing.

Simplicity was not just a technological limitation. It was a creative necessity. If Sakamoto were given additional verbs outside of shoot, jump, run, would he have created Metroid? I’d argue no. He might have made a great game, and that game might have instead become the subject of this essay, but it wouldn’t have been Metroid. The idea that restrictions breed creativity is not a new one. An early famous example credits Ernest Hemingway with creating a story using only six words: For Sale. Baby shoes. Never worn. More recently, the Creative Director of What Remains of Edith Finch told me in an interview for the Masters of Unlocking podcast that the bright light transition between scenes that I interpreted as a visual nod to infinity—an idea that permeates the game—is more likely a result of the development team simply being good at programming those transitions. So much for authorial intent.

![]()

Back to the overzealous profiteer game makers I mentioned earlier. The video game industry at the time of Metroid’s release in 1986 was just coming down from a three-year financially disastrous party binge, suffering revenue drops from $3.2 billion in 1983 to about $100 million in 1985. In today’s terms, this would be the equivalent of going from a lot of money to not a lot of money. I hope my explanation was helpful.

This market downfall—dubbed The Atari Shock in Japan, The Video Game Crash everywhere else, and The It’s-Not-My-Fucking-Fault! to Howard Scott Warshaw[3]Howard Scott Warshaw designed the movie-based E.T the Extra-Terrestrial Atari video game, which is considered one of the causes of the video game crash. Warshaw was pressed to develop the game in … Continue reading—understandably forced video game developers to reevaluate their futures. This, I like to pretend, is why Metroid does not dive fully into the world of coke-addiction. Sure, technical limitations and shaky market conditions are the more likely reason to avoid pivoting away from simplistic story into uncharted narrative depth, but if I’m going to imagine a world where Samus Aran and I are spiritual siblings, I’ve got to embrace some elastic assumptions. But I can’t blame Nintendo for instead going the tried-and-true route of guns + space = fun, even though it discredits my notions of a shared heritage.

Besides, what sort of late game boss fight could accurately represent my adolescent years, anyway? The battle between Zit Boy and Angry Shaft culminating in a level 9 climax in the Masturbatorium?

![]()

The industry wasn’t completely unfamiliar with drug use, however. The stories of a Nolan Bushnell helmed Atari being rampant with drug use is well-documented. And on the software side, by 1986 we already had Pac-Man, a game whose primary objective is to choke down enough pills to not only see ghosts but to attempt to eat those ghosts. And let’s not forget that arguably the most famous video game character ever, Mario of Super Mario Bros., constantly gobbled down amanita muscaria mushrooms. This fungi is known for causing the perceptual phenomena micropsia which causes objects to be perceived as smaller than they actually are, thus giving the user a sense of being larger than normal. Additional side effects include increased stamina, crashing through brick walls, and suffering thirty-one levels worth of blue balls while a toad person flips you the double-bird.

Drug use in video games had to remain subdued and subliminal. I understand. Video games were a product created by an industry that at the time catered to children. Though video game aficionados—as I was eventually to become—sensed something grand with the medium, the industry and consumers alike at the time sold and bought home console video game systems primarily as toys. They were Christmas gifts. They were rewards for perfect report cards. They were, as I was soon to learn, a rare token gesture of obligatory quinquennial paternal affection. Video games were by necessity, due to hardware limitations, simple enough for a child: shoot, jump, run. My father was, due more likely to software limitations, also simple, and his priorities equally so: shoot, jump, run.[4]That was a lack-of-intelligence joke, by the way. I explain it here in case you also have software limitations.

![]()

The original Nintendo Entertainment System (NES) home console was released in North America in 1985. I was three years old. My mother and father were already many miles mentally deep into their 1988 divorce. That, paired with my age-appropriate focus on the difficult transition from shitting in diapers and bathtubs to shitting in toilets, meant that tech-savvy first-adopter status wasn’t a concern. So my relationship with Metroid started later than it did with other kids at the time.

It was seven years later—six years after the release of Metroid, I was ten—that a package arrived at the trailer home where I lived with my mother and two sisters. Even stranger than the appearance of an unexpected package (this was before the time of anthrax and pipe bombs, so without those associations a strange package was truly a mystery) was the identity of the sender: my father.

By that time my father had become—and I had accepted him as, perhaps even preferred him as—a rotating gift dispensary with odds not unlike post-beer-binge dumps; I didn’t know when to anticipate the arrival, but when it happened there was usually a token reward and relief despite the general unpleasantness.

I’ve found through conversations over the years with children raised in traditionally termed “stable” homes—homes with both parents present, in love, and eager to collectively raise well-adjusted children—that it’s difficult to comprehend how easy it was for me to cut myself off from my father. Sure, for the first ten years or so, during his total 2-3 visits, 12-13 total phone calls, and one mysterious package delivery, I questioned the separation as any child in my situation might. I wondered who was to blame for the separation. I wondered if we’d ever be a family again. But truly—though my mother may have a different story—I don’t recall ever actually missing him. I somehow understood that he was a bad man with a history that I didn’t want to be a part of. He was the villain. My mother was the hero.

Narrative simplicity.

![]()

Strangely, that gift spawned what would become one of the most enduring loves of my life: video games. High school and college were equal parts studying, drinking (alcohol in college, Surge soda in high school), cartoon watching, and gaming. For a while, my career aspiration was to design video games. I was obsessed. Though the obsession died down considerably over subsequent years I eventually, in my early thirties, succumbed to the nostalgia bug and purchased an NES console on eBay. One of the first games I re-acquired: Metroid.

Playing the game today, I’m every bit as terrible as I was in the early 90s. Terrible, in terms of the game’s primary objective, anyway. In terms of over analyzing the game’s presentation and intent, I’m much more capable. The seemingly endless corridors, dark, blue, and almost visibly damp, are punctuated by the heavy suction of Samus’ boots as you guide her horizontally across the screen. Native species—I hesitate to say “enemies”—navigate the floors and walls along set paths, not toward you, not away from you, but according to their own unknown and apparently passive agendas. It’s only when you venture further into the unexplored planet that you’re met with any hostility. Bat-like enemies dive from the ceiling. Though you are armed with a short-range blaster cannon, should you choose not to engage the diving natives, they will explode after a few seconds, sending bodily shrapnel in four directions. This is the suicidal behavior of an animal out of options, the last effort to do something, to do anything, to prevent its home world from being conquered. You are, simply put, an intruder.

You mission isn’t without some merit. The planet, Zebes, is the base of operations for a gang of space pirates who plan to use one of the local fauna—a life-draining parasite and titular metroid—as a biological weapon. But all the passive citizen deaths prior to your climactic battle with the leader of the space pirates feels unnecessary and cruel. And in this case, we cannot allow technical limitations to explain away the violence. “Perhaps programming artificial intelligence—even as basic as guiding an enemy to a player—is too much for the NES hardware,” you say. Not true. When you do encounter the metroids, near the end of the game, they have no issues navigating directly toward the player. The metroids have a mission to kill you as quickly as they possibly can.

And quickly kill me they did. To this day I haven’t been able to complete Metroid.

Abandoning this game feels appropriate. I’ve long accepted that my father isn’t interested in a relationship with his children, so positioning a video game as offering symbolic closure to a lifetime of absence would be hollow. And worse, manufacturing such ceremony would surely add unnecessary baggage to my love of video games. Would each colossus in Shadow of the Colossus then earn me one hug credit? Would the scale of my journey in The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild now reflect the scale of my own journey for a father’s love? Would my choice of faction in Fallout: New Vegas now have a new implied root motivation?[5]Given my father’s cocaine history, perhaps joining the Followers of the Apocalypse and completing the “High Times” mission tree would make sense. Is my father somehow inextricably linked to video games and therefore my obsession with them an obsession, to some degree, with my father?

No.

Though it may be true in an armchair therapist kind of way that NES = father’s love, I’m old enough and rational enough to disassociate my affection of the game console with any lacking paternal affection.

But that’s not going to stop me from having some fun. Join me as I look back on Metroid and attempt to extract psychology from motive.

Therapy Topic #1: Metroid/fatherhood is fucking difficult

Metroid is considered by many to be one of the most difficult NES games. It’s not Ghosts n’ Goblins difficult, or even Contra difficult, but neither is it a walk in the Sara Parker’s Pool Challenge.[6] Truth: I don’t know if Sara Parker’s Pool Challenge is actually easy, but it’s one of the few NES games with “park” in the title and therefore sufficient to complete my “walk in the … Continue reading

One of the main reasons the game is so difficult is that it lacks an in-game map, leaving the player to spend most of the game aimlessly wandering through mazes and corridors that aren’t often distinct enough to make the necessary spatial impression to a young, not fully cognitively developed boy. It’s poetic I suppose that aimless wandering and a general ‘in over your head’ mentality pervades the very game that a deadbeat father gifted to his ten-year-old son five years post-divorce.

Therapy Topic #2: The music of Metroid/fatherhood is cold and desolate

Metroid’s simple, empty opening tune is the first thing that comes to mind still today when I try to explain the meaning of dirge to someone[7]The fact that I do have plenty of opportunities to define what is basically a funeral song says a lot about the kind of social discussions I wedge myself into.. The song is minimal, even by the 8-bit standards of the day. But unlike the general kid-friendly, upbeat peppiness that most games were able to create even given the console’s hardware limitations, the Metroid title theme insisted on being defiantly and objectively haunting.

Had the emo persona been a known possibility during my pre-teen years I very well may have succumbed to the allure of the black clothes, black eyeliner, white skin aesthetic. Unfortunately, emo didn’t exist, at least not as a viable option in my small town where any outlying spike of couture personality meant embarrassing your mom enough to have her exiled from the only bar in town. I wasn’t going to do that.

So, in lieu of emo I listened to the Metroid theme.

Give the song a listen. Then hug your dad.

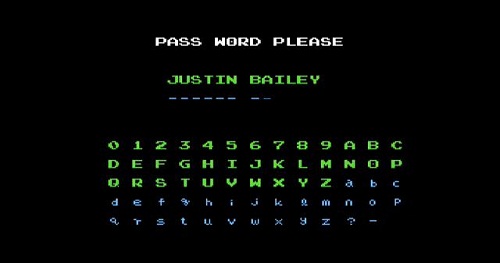

Therapy Topic #3: There are ways to cheat in Metroid/fatherhood, but it takes all the fun away

Given Metroid’s difficulty, the only way I was ever able to squeeze any real enjoyment from the game was to use a cheat code. Fatherhood is difficult too. I suppose then I can’t blame my father for attempting to use the ‘give the kid a video game’ cheat code to make up for bypassing all that pesky child raising crap.

The Justin Bailey cheat code is certainly one of the most well-known in all of video game-dom, ousted perhaps only by The Konami Code. But where The Konami Code usually rewarded the cheater with more lives by which to have a better chance at beating a video game, the Justin Bailey code effectively allowed the player to explore the planet Zebes as a post-war tourist with only the final boss remaining. Meaning: you’re not playing a game anymore; you’re exploring the aftermath. Essentially, it’s a stupid cheat code that serves only to grant the lazy player a façade of accomplishment similar to post-natural-disaster political photo-ops.[8]I’m not sure what political figure/natural disaster combo this joke is mean to skewer. By the time this article sees publication, you’ll likely have your pick of many.

Therapy Topic #4: Samus Aran is a girl, and I don’t know how to be a man.

I don’t like sports. I can’t drive a stick-shift. I don’t eat much steak. Even today am not sure if I’m shaving correctly. I’m not the stereotypical man.

How appropriate then that the video game gifted to me by my father would be one famous for having a female as its playable character?

Female playable characters weren’t new in 1986 when Metroid was released, but they definitely weren’t common. Scarcity of the female lead, along with Therapy Topics 1-3 above, might be enough to warrant therapist leeway should I ever have gender confusion issues, but scarcity alone isn’t what makes Metroid’s female lead unique. Rather, what makes Metroid special is that the player is never made aware that Samus Aran is a female. In fact, it’s only by either 1) beating the game in less than two hours and seeing Samus bikini-clad as a reward or 2) using the Justin Bailey cheat code that a player is ever encouraged to consider a pixelated vagina.

![]()

As I write this, my son is playing the eBay acquired NES. He’s four years old. He’s playing Super Mario Bros. He’s terrible at it. But every time he touches a Goomba, every time he falls into gap, every time a Koopa Troopa bumps into him, he turns to me, sees that I’m watching him play, and that’s good enough for both of us.

If you liked this article, please share it. Please! It would mean the world to me.

Why not help me out? Tweet using one of these pre-composed tweets by simply clicking a tweet below.

Can Metroid (on NES) make @calebjross a good father? Find out here https://calebjross.com/in-lieu-of-emo-i-listened-to-the-metroid-theme/

Read a funny take on Metroid and fatherhood from @calebjross a learn a bit about the history of NES https://calebjross.com/in-lieu-of-emo-i-listened-to-the-metroid-theme/

Footnotes

| ↑1 | Believe me, I know how much this sounds like b-movie set dressing and therefore simply cannot be real. But I assure you, these tropes are real. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | We as a culture didn’t yet have the ethical flexibility to render domestic malfeasance in 8-bit graphics. That wouldn’t be popular until the 1988 port of Double Dragon when kids the world over witnessed a female get gut-punched within the game’s first 10 seconds. |

| ↑3 | Howard Scott Warshaw designed the movie-based E.T the Extra-Terrestrial Atari video game, which is considered one of the causes of the video game crash. Warshaw was pressed to develop the game in only six weeks to ensure production in time for the 1982 Christmas season, which disappointed children the world over remember as the magical day they stopped believing in Santa Claus. |

| ↑4 | That was a lack-of-intelligence joke, by the way. I explain it here in case you also have software limitations. |

| ↑5 | Given my father’s cocaine history, perhaps joining the Followers of the Apocalypse and completing the “High Times” mission tree would make sense. |

| ↑6 | Truth: I don’t know if Sara Parker’s Pool Challenge is actually easy, but it’s one of the few NES games with “park” in the title and therefore sufficient to complete my “walk in the park” joke. |

| ↑7 | The fact that I do have plenty of opportunities to define what is basically a funeral song says a lot about the kind of social discussions I wedge myself into. |

| ↑8 | I’m not sure what political figure/natural disaster combo this joke is mean to skewer. By the time this article sees publication, you’ll likely have your pick of many. |