Being a Ninja is Easy in a World Full of Idiots

(If you’d rather read this essay on your Kindle, you can do so by clicking over to the Kindle store right now)

How a Stolen PlayStation and Tenchu: Stealth Assassins Taught Me that Gamers Don’t Want Realism

In high school, sometime during the year I finally admitted my distaste for the Beastie Boys, I arrived home one afternoon from school to find the front door of our family’s rented duplex open. The gap was wide enough to register from across the street, wide enough to skew the house’s facade. Like skipping frames. Like a network lag.

I didn’t realize it until that moment, but in every memory of every house I’d ever lived in, the front door is closed. The house we rented on 4th street—we moved because its owner sold it—that house’s front door is sealed. The white house on Ellinwood—we left when the owners increased the monthly rent by a week’s worth of groceries—its door is closed. The apartments in Dogwood, too. And the country house. All of these homes, though temporary they were amid a childhood of raised rents and self-interested landlords, were safe. Doors closed.

The open door that afternoon infected my memory. The open door was a crooked picture frame. It was a hallway rug left dogeared upon itself. The open door was a glitch in the Matrix.

Nobody was supposed to be home that day. It didn’t make sense.

I crossed the street and approached the concrete slab porch, the same one I hopped down just that morning. Spiderwebs stretched above from the leaky gutter down to the wiry metal banister, bobbing to the early spring breeze. If the web were a boat sail the small, crumbing porch would be fighting its moor. The spiders had homesteaded the area months ago. We let them stay not out of some benevolent appreciation for all things living but because nobody in my family was brave enough to risk swinging a broom, missing, and wondering forever-after when the spiders would seek revenge.

So we allowed the spiders their nook on our porch. And though they were respectable neighbors, they weren’t protective neighbors. Their disinterest in the open door felt traitorous. But then again, for a creature whose entire home is subject to the atmosphere’s whims, a door left ajar is inconsequential.

So we allowed the spiders their nook on our porch. And though they were respectable neighbors, they weren’t protective neighbors. Their disinterest in the open door felt traitorous. But then again, for a creature whose entire home is subject to the atmosphere’s whims, a door left ajar is inconsequential.

The noble version of Caleb would claim to have first been concerned about the welfare of his family. If the open door was a result of forced entry, and if my family were home at the time, would they be okay? But my expectations had been compromised by television forensics shows where phones ring with the bad news seconds after the crime, and though our real world lacks the TV world’s jump cuts, I still felt the cosmos would at least ping my gut if my family were in danger.[1]Yes, the very same cosmos that allowed the home invasion in the first place.

Those same forensics shows had taught me that a burgled home was a destroyed home, so imagine my surprise when upon entering I found no toppled lamps, no shattered cabinet glass, not even a single bedspread left disheveled by a hunt for jewelry hidden between mattress layers or beneath pillow cases. In fact, my home appeared untouched.

But then I entered my bedroom and found my prized possession gone—my PlayStation. And in its place a clean PlayStation-shaped rectangle of carpet.

I was determined to find the thief. And to help me: the stealth and investigative skills honed by more than a year spent playing Tenchu: Stealth Assassins, the most realistic ninjitsu-based videogame ever developed. Right?

![]()

The Sony PlayStation was my first major purchase after landing a part-time, after-school job at a grocery store in 1998. Todd’s IGA was local in the sense that everything is local in a town of 3,500 people. But still, at one mile from home, the walk was just distant enough that a car would have been a more logical first purchase. But could a car play Tenchu: Stealth Assassins?

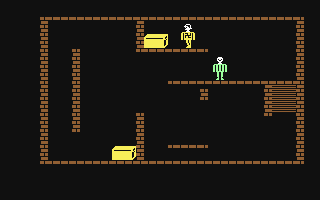

Released in 1998, Tenchu: Stealth Assassins was advertised as being the first truly immersive ninja game with a focus on stealth. Prior to Tenchu, ninja-obsessed kids like me satiated our urges with years-old standbys like the aggressively non-stealthy Ninja Gaiden series, the Shinobi series, and Castle Wolfenstein (1981) and Beyond Castle Wolfenstein (1984) where the world first tasted stealth.[2]Some argue that Pac-Man is a stealth game. Those people are stretching it. Stealth gameplay in 1998 wasn’t yet mature enough to have its own legacy, though 1998 was arguably the start of that legacy. Thief: The Dark Project and Metal Gear Solid were also released that same year. Stealth was on its way to becoming a categorical mainstay like Platformer, Action, and Sports.

Tenchu’s impact on me was huge and immediate. Following the very first time I even heard about the game (a commercial on TV) I called my mother and begged her to drive me to the nearest town with a store big enough to sell videogames (Topeka, a 45-minute drive away). My request shouldn’t be considered light. I was asking my single mother of three to not only find time among her three jobs to spend valuable gas on a trip to allow me to blow my money on something subjectively trivial, but I was doing so without any consideration for the money management skills an after-school job should be teaching me. From her perspective, I was just an immature kid with an immature request.

But I think my mother knew something about me that even I didn’t yet know: videogames were important. Generally, I tampered any selfish request with a level of respect for my mother and her difficult plight, but the fervor (ie, crazed annoyance) of this particular request must have clued my mother into a need deeper than simple entertainment.

![]()

That first Tenchu commercial represented to a young, ninja-obsessed Caleb the first time the mainstream entertainment world seemed to get ninjas right. The United States cultural understanding of ninjas is born of pop-culture mythos propagated by anime, b-movies, and videogames. The modern ninja is a copy of a copy of a copy of a feudal Japanese spy. This information degradation is how we’ve all come to believe that ninjas could pop enemies like over-inflated balloons with a single sword strike (see: Ryu in Ninja Gaiden), could conjure a protective shield of lightning (see: Shinobi), and could leap 40 feet into the air to land softly on delicate tree branches (see: The Legend of Kage).

But of course ninjas couldn’t actually do any of these things. Ninjas are more aligned with modern-day magicians than modern-day superheroes. I knew this even as a young Caleb. I was incapable of playing ninjas with kids at recess because kids at recess didn’t want to blend in with their surroundings. They didn’t want to sit idly at the playground parameter to learn the natural routine of our enemies/classmates so that those routines could be leveraged to meet some silent, non-violent mission success criteria. Kids didn’t want to meditate when there were soccer balls to be kicked and squares to be foured. Imagine how frustrating it was for me to explain to a hyperactive group of fourth graders that we had to be quiet and listen to the wind.

Watching martial arts movies with me was a painful experience. Where other kids could simply enjoy the absurdity of a fully-clad ninja in broad daylight, I felt personally betrayed by Hollywood. For me, the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles movies weren’t problematic due to the giant, anthropomorphic turtles. No, my willing suspension of disbelief dissolved by way of the Foot Clan, a gang of flamboyantly dressed purported ninjas who comfortably robbed electronics stores in broad daylight. Same with 3 Ninjas and Snyder’s gang. Same with Beverly Hills Ninja, which was specifically about the bumbling futility of a ninja in modern day environments.[3]Though the bumbling part is more due to the physical comedy of Chris Farley than the modern environment. “The comedy genre shouldn’t be devoid of respecting the ninja ethos!” I wanted to yell (and probably did).

With that first viewing of the Tenchu: Stealth Assassins trailer on TV I sensed a shared lexicon. I would no longer have to correct classmates by citing the many ninja books on my bookshelf. By the time Tenchu was released, I was too old to be playing ninjas at recess, but my desire to annoyingly correct people on their ninja misconceptions was still in full force. With Tenchu, I could point to a common referent and proclaim proudly: “I told you so!”

![]()

The PlayStation’s disappearance was, according to my forensics television education, a clue. The thief knew what he was after. A deeper survey revealed a few rings missing from my mother’s dresser and a jar of pocket change gone too. But those ancillary finds were within grabbing range en route to the true target, so their disappearance was certainly one of convenience.

At that age, seventeen, I was late to give up fantasy. I still believed fingerprints were a 100% accurate way to identify criminals. I still believed all people on death row were guilty. I still wanted to believe that Spider-Man’s web shooters could be real. I believed in an elegant simplicity, the ninja’s ability to see things others didn’t see.

To let someone steal from me was a failure. My years of schoolyard meditating and Hollywood critiquing were worthless. Having my PlayStation stolen was an affront to my inner-ninja.

I searched my bedroom for evidence, eventually finding a single short, curly hair near the TV. The hair matched that of my suspect #1, a guy I’d been on-and-off friends with for a few months. I bagged the hair using a polypropylene sports card sleeve and presented the evidence to my mother. To my surprise, she refused to pass the clue on to the police.

My mother was never one to be direct with life lessons so had I pressed her to explain her refusal, she would have obscured the truth by citing our small town’s limited resources as the primary reason why she didn’t want to bother the police department with a DNA analysis of a single hair.

But she knew the truth. She offered instead a look that rolled together disgust, sadness, and pity, from which I extracted a jarring reality: I was holding a pube.[4]”All right, let’s match this up against the collection of pube samples we’ve taken over the years.” You know, when a criminal gets booked for a petty theft crime misdemeanor the … Continue reading

Innocence to revelation, like puberty whiplash.

It was in that rolled look from my mother that I learned what game developers have always known: Fantasy is fantasy. Reality is reality.

![]()

Tenchu promised to scrub clean the sorcery and honor practicality. But the renegade pube taught me that a true ninja game would be impossible.

While Tenchu: Stealth Assassins rewards players who favor stealth movement and silent kills, it equally allows—without punishment—hack-n-slash gameplay. This infuriated me. I was willing to stomach the flat, Midwest American-accented Rikimaru as a believable enough protagonist, but when he, upon a “silent” kill, spends a few hundred frames of animation in celebratory posturing, I deflate. The dance is not only flamboyant enough to rouse the attention of heretofore ignorant guards, but also unskippable. This was inappropriate.

But I never voiced my disapproval. When friends at school asked about the game, I praised it as authentic. I’ll admit, today, many years later, that I qualified my defense of the game by deflecting to other, actually separately-noteworthy elements. They’d ask about the stealth, and I’d pivot to the game’s level design. Tenchu clouded its environment’s middle distance with darkness. This saved expense computing resources but also fostered an intimacy that reflected the game’s themes and electricity-less time period. A bug became a feature. Narrow cave corridors and claustrophobic forests accomplish the same end for the same reason. This use of environmental level design to hide the PlayStation’s draw distance limitations would be praised more overtly with the following year’s horror masterpiece Silent Hill. Just replace shadow with fog.

Tenchu’s ninjas had swords. Most real ninjas likely didn’t carry swords.

But playground-me: “the swordplay is awesome!”

Tenchu’s ninjas were able to zip from the ground to a rooftop in seconds using a grappling hook. That real ninjas used grappling hooks to climb is a reasonable belief. That real ninjas could use those grappling hooks to zip up-and-out of heated melee combat leaving their opponents confused and apparently unable to look up is nonsense.

But playground-me: “the grappling hook is awesome!”

Tenchu’s ninjas fought clans of other ninjas. Real ninjas would have little reason to infiltrate other ninja strongholds.

But playground-me: “it’s noble the way you fight the evil, misguided ninjas. Also, it’s awesome!”

Why was I willing to defend the game when I’ve trashed so many pieces of media for less? Simple: I was invested.[5]Also, I was bad at the game. Very bad. Traumatically bad. Here was a game I was uniquely primed to dominate, yet I failed. No way was I going to let anyone find that out. Buyer’s remorse is a powerful motivator of silence. This game was meant to vindicate me. Instead, it only validated what game developers have always known: nobody really wants to play a game based on the true life of a feudal Japanese ninja, because a real ninja carried out assassination missions with dream-crushing rarity. Game developers knew that listening to the wind would be a terribly unfun game mechanic.[6]To be fair videogame ninjas are bullcrap in the way that all real-life occupation based videogame characters are bullcrap. Overcooked doesn’t attempt to portray the actual experience of a chef … Continue reading

![]()

It’s not that videogames and movies didn’t know how to properly depict real ninjutsu. It’s that videogames and movies knew that real ninjutsu wouldn’t make an engaging piece of entertainment.

Realism is often thought of as a videogame ideal. Realistic visuals. Realistic characters. Gamers purport to want realism.[7]Or, perhaps game publishers want gamers to want realism. If publishers push realism, then they can compete on technology rather than creativity. But that’s a topic for another time. In a way, this desire aligns with the innate human need to categorize and compare. Because we all have access to an infinite library of real world references—just look out your window—it’s less cognitively expensive to measure the success of a game against the known real world we live in than to measure games against an intangible goal of a game developer. This is the same logic that causes movie audiences to compare the performance of a lead actor in a biopic to the real-life inspiration rather than speak to the actor’s talent in-and-of-itself. “Wow, Jamie Foxx looked and acted just like Ray Charles” vs “Wow, Jamie Foxx emoted so well.”

Thankfully, as videogames mature and technology gets better, visual realism becomes commonplace. This gives developers the freedom to explore outside of the visual realism ideal. To me, this partially explains the resurgence of pixel-based sprites in recent years.[8]Widespread access to development tools and the simple nostalgia of maturing game developers also contributes. Basically, as visual realism continues to get boring, gamers will further accept narrative and mechanics over visuals. Social cycle theories abound in game design trends.

But when game design’s trending sine wave hits a plateau where visual realism dominates, the ludic contract and the anthropomorphic contract don’t play nice. This tension between the realism videogame players want from their enemy characters and the lack of realism players need from their enemy characters, I’ll call ludo-anthropomorphic dissonance.[9]Not to be confused with ludonarrative dissonance, which is even more fun to say.

![]()

An important strategy in Tenchu: Stealth Assassins is lure guards away from their posts by tossing poisoned rice balls in their direction. What kind of idiot guard is so willing to ditch their security responsibilities for edible litter? The correct answer is of course the kind of idiot guard created by a smart programmer.

A truly intelligent enemy NPC (non-playable character) is not what gamers want. Gamers don’t even want artificial intelligence. Gamers want scripted behaviors based on shortcut heuristics with game balance—not realism—being the end goal.

And to be fair, enemy AI (artificial intelligence) in videogames is a bit of a misnomer. True AI implies machine learning, but videogame enemy AI is really just a collection of scripted behaviors that account for a bunch of different enemy states. For example: if the player is within x pixels of enemy, then the enemy enters the hunting state. If the enemy’s health is below y%, then the player enters the flee state.

But back to Tenchu and why watching an enemy chase down a suddenly-appearing ball of poisoned rice is funny. Because we recognize this character as human, we are encouraged to expect human-like behavior from it. And chasing a materialized rice ball without question is not human-like behavior. So, it’s funny. This exemplifies what’s called the Benign Violation theory of humor: Things are funny when they subvert our expectations but only when they don’t hurt anyone. This guy isn’t a real person. Nobody was hurt. It’s okay to laugh.

But imagine if this enemy character looked more human-like. Then, the rice ball chase elevates from being funny to being hilarious. The Metal Gear: Solid series embraces this dissonance. Of the many stealthing methods available to the player, the simple cardboard box is the most well-known and discussed. The player can, at any time, hide from enemies using a cardboard box. This strategy is applicable—and hilarious because of it—despite most of the game environments being incredibly hi-tech, implicating the duped guards as being smart enough to know better. Realistic looking enemies + convincing enemy behavior + absurd cardboard box disguise = hilarious.

But, interestingly enough, because of the realistic portrayal of the human-like enemies, our laughter is curbed slightly. Benign Violation is tampered when we’re meant to be invested in what’s being harmed, even if only superficially. That’s why laughing at a news story about mass murder is sociopathic behavior. And maybe why bullies who laugh when they make kids cry should be taken to therapy.

But gamers demand so many conflicting things. We want realism, but we also want enemy AI to respect our need for fun, meaning we don’t want our enemies to be super smart. We need our inept guards to eat discarded poisoned rice balls. We need our machine gun-toting soldiers to ignore a conspicuous cardboard box. Otherwise, the game wouldn’t be fun.

![]()

Soon after my PlayStation was stolen I invested another wad of grocery-store cash into another PlayStation. I re-purchased several games, but Tenchu: Stealth Assassins wasn’t one of them. It wouldn’t be until years later that I’d play the game again. Those elapsed years ushered in the PlayStation 2 era, which marked a leap forward in terms of visual realism. The PlayStation (PS1 it came to be known as) was archaic, and Tenchu existed as one of the many laughable attempts to chisel realism from harsh angles and minimal polygons. To have been angry at the way Tenchu rejected realism felt later like a symptom of simple immaturity. Of course the game isn’t supposed to be 100% true-to-life.

But that’s what maturity is. One day, you realize the the hair in your hand is actually a pube.

Other resources:

Footnotes

| ↑1 | Yes, the very same cosmos that allowed the home invasion in the first place. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Some argue that Pac-Man is a stealth game. Those people are stretching it. |

| ↑3 | Though the bumbling part is more due to the physical comedy of Chris Farley than the modern environment. |

| ↑4 | ”All right, let’s match this up against the collection of pube samples we’ve taken over the years.” You know, when a criminal gets booked for a petty theft crime misdemeanor the police take a thumbprint, a mugshot, and you know, pluck a few pubes and deposit them in a small little pube sample bag to keep on record in case that criminal ever decides in the future to become a naked thief. “Gotcha. Naked thief. Thought you could get away with it. Nobody ever expects to be foiled by the pube repository.” |

| ↑5 | Also, I was bad at the game. Very bad. Traumatically bad. Here was a game I was uniquely primed to dominate, yet I failed. No way was I going to let anyone find that out. |

| ↑6 | To be fair videogame ninjas are bullcrap in the way that all real-life occupation based videogame characters are bullcrap. Overcooked doesn’t attempt to portray the actual experience of a chef because that would be boring. |

| ↑7 | Or, perhaps game publishers want gamers to want realism. If publishers push realism, then they can compete on technology rather than creativity. But that’s a topic for another time. |

| ↑8 | Widespread access to development tools and the simple nostalgia of maturing game developers also contributes. |

| ↑9 | Not to be confused with ludonarrative dissonance, which is even more fun to say. |