Exploding the Small Things for Fun

How small can you make a thing and still have that thing be interesting?

I’ve been told throughout my life spent creating things (books, video games, YouTube videos, podcasts) that simplicity is a core ingredient of creative output. When a thing is simplified enough, when it’s abstracted to its core requirements, when the guardrails are robust and the lanes clearly defined, that’s when creativity tends to flourish.

I embrace the challenge, and in fact, when a thing is simplified, that’s when I discover an interest enough to justify the very act of creating. Not until all magic has been stripped away am I able to see the potential for magic.

This is how I learned to appreciate genre fiction, for example. I still don’t read much of it (there are other types of fiction I like more) but an author who must simultaneously honor audience expectations and subvert those expectations to surprise, delight, and (probably) retain interest, is a concept I respect.

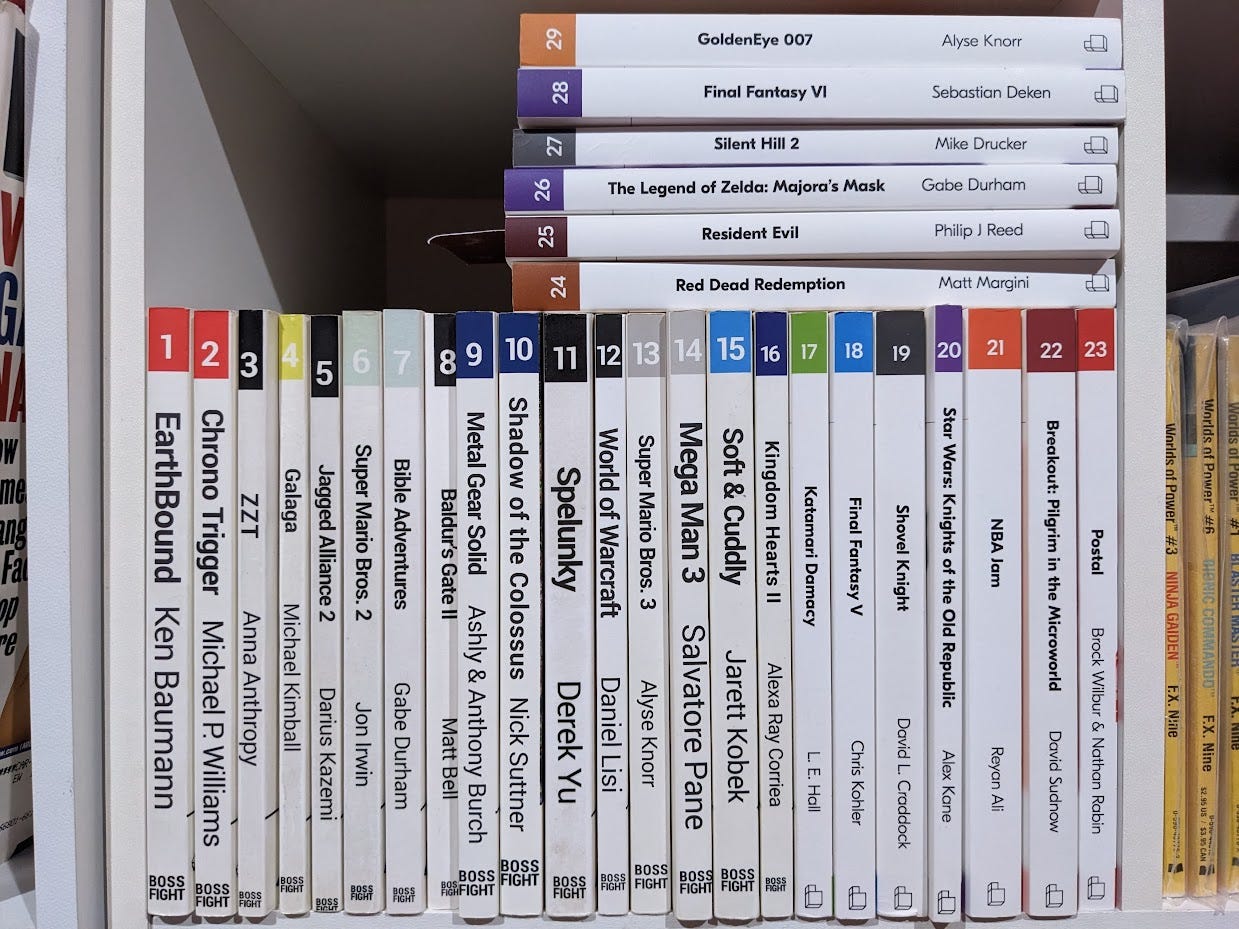

Years ago, decades maybe, I heard about a new book imprint called Boss Fight Books. At the time they had yet to publish anything, but they promised a series of books, each one dedicated to a single video game. An entire book = one video game. The audacity intrigued me.[1]Though a bit of research suggests that the publication I heard about all those years ago, in college, so at least before 2006, could not have been Boss Fight Books. Oh well, I still champion BFB for, … Continue reading

Years go by, I forgot about Boss Fight Books, until the press resurfaces amid the video game milieu that my gaming friends and I have subsisted upon as a shared space for all those years since. Word of this “video game press that publishes books about single video games” percolated amid our shared social threads. That seed planted years ago found sunlight.

Twenty-nine books later, I’m still a fan of the press; never wavering. The novelty still excites me. An entire book = one video game. Wow.

I read a lot of books about video games, but those that focus on single games (even game’s I’ve never played, even never heard of) dominate my time. Reference texts that promise to catalog entire generations of games don’t excite me at all. Interview compilations are fun enough but tend to lack a narrative structure. Histories of single companies are nice, but they don’t get specific enough. Instead, I want to roll a grain of sand between my fingers and forget about the beach for a few hundred pages.

Perhaps “simplicity” is the wrong term. By reducing the scope of a thing, the guardrails shrink too, meaning the author must be extra clever to mine and smith an interesting story as that space around their subject narrows. “Simplicity” maybe implies a vacuum where creativity isn’t welcomed. Maybe, I’m thinking “fragments?” Or maybe a “constituent,” like how politicians frame the citizens of their jurisdictions as pieces that have authority over their whole. No, no, I like “fragments” better.

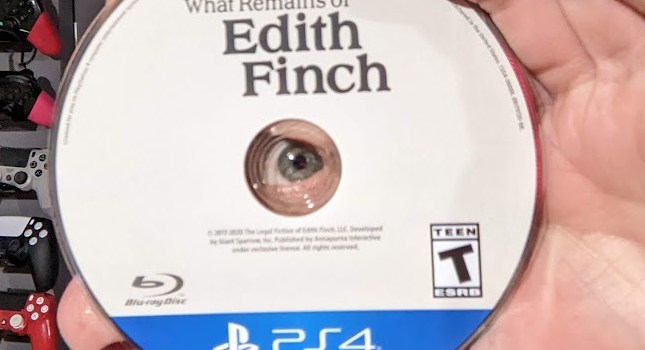

I’ve been working on my own fragment story. About a year ago I started writing a book about a single video game. What Remains of Edith Finch is, by video game standards, a “simplistic,” stripped-down representation of what a video game can be, so much so that the game might have trouble even contributing to a definition of “video game.” What Remains of Edith Finch is a walking simulator, which, for brevity’s sake I’ll say is a video game that favors story and exploration over mechanics and combat. There’s neither a win nor a lose condition. So, not really a game.

The challenge intrigued me. How will I write an entire book about such a simplistic game (with a playtime of about 2 hours, by the way), with very little history to lean on (it was released in 2017), and from a developer with only one other previously-released game? How can I see into the silica and oxygen of the grain of sand with enough passion and persuasion to dull the allure of the beach surrounding it?

My own personal interests, for sure, certainly pushed me to strip away the rest of the beach. Single phrases, presented in the game as diary entries, inspired full paragraphs. My own interest in game development encouraged me to peek beyond the game boundaries enough to satisfy a strange obligation I felt to include developer stories in the book.[2]I like reading developer stories, but, well, I’m shy and awkward so interviewing people is something I don’t look forward to…but, for my What Remains of Edith Finch book I did it anyway, a … Continue reading So, me being me (the only form I know how to take on) made me care about the core fragment of the thing.

But what kept me invested in writing the book—and what I was finally able to identify as my main attraction to most Boss Fight Books—is that the more powerful a microscope I applied to the subject, the more I leveraged my own personal history and stories to explode out the subject. The more granular the subject, the less objective history can be applied to it, meaning a higher reliance on subjective history, which is the history type I prefer to read.

Zooming in requires subjectivity to make the minutiae interesting. This was a big revelation for me. It allowed me to stop apologizing for my love of personal stories over objective history.[3]And for anyone who has played What Remains of Edith Finch, you can perhaps now understand why I was so drawn to the game’s themes of subjectivity.

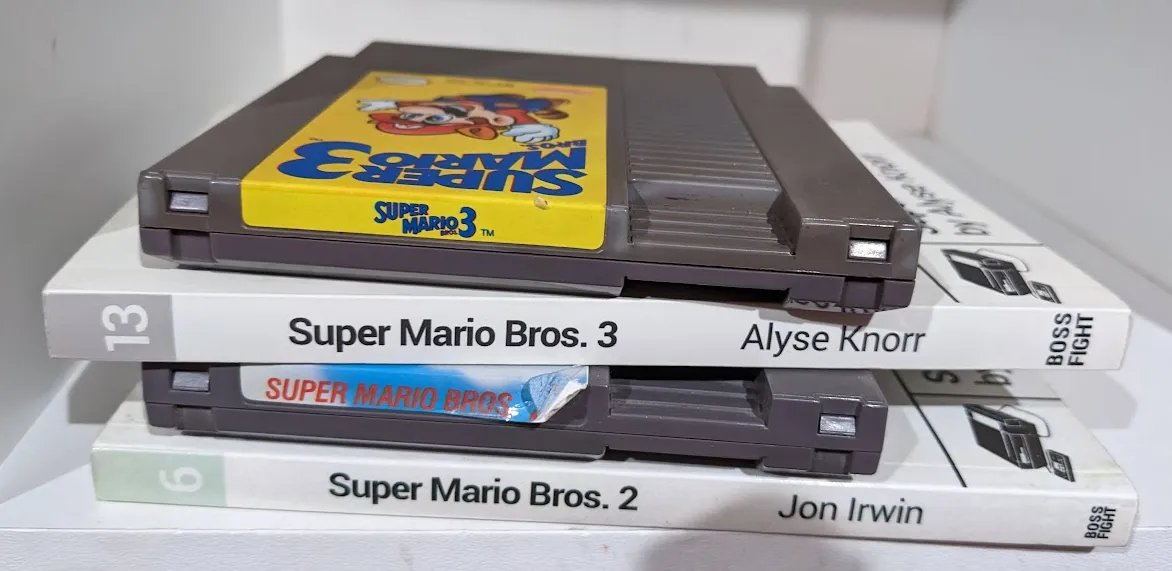

The first Boss Fight Book, about Earthbound, by Ken Baumann, leans heavily into the author’s own life. It’s a memoir by way of video games as a landmark. It’s easy to read this first book as an untested “what if” on the concept of video games as a referent point for self-reflection. And it’s not at all apologetic. I like that.

As the Boss Fight Books imprint grew its catalog, the books would distance themselves from personal stories and lean hard into documenting history. Personal stories still existed (Galaga by Michael Kimball is almost 100% personal history, and is told in a unique, fragmented style, which seems fitting given this article; Breakout: Pilgrim in the Microworld by David Sudnow is a reprinting of a book from 1983, which feels like it must have been some sort of osmosis inspiration for Boss Fight Books; Postal by Brock Wilbur & Nathan Rabin is part history and part gonzo journalism). But over the lifespan of Boss Fight Books those personal stories slowly subsided in favor of something more…sterile.

I harbor no ill-will toward Boss Fight Books’ change in direction. I still eagerly absorb every word they publish.

For my book about What Remains of Edith Finch I wanted to—and perhaps, had to, given the narrow scope of the subject game—see how much of myself might be exposed when reflected against the game. Video games are important to me. Very important. I cling to video game worlds as a compulsion, bypassing even the slightest consideration that video game worlds aren’t real. It’s not absurd for me to map my life in tune to the changing of console generations or to retrace my life along the evolution from pixelated characters to motion-captured adults outfitted in ping-pong balls playacting adjacent a foley stage where serious adults twist stalks of celery to capture the sound of a snapped ulna. Without video games, my life’s map would lack its most important waypoints. The fiction of video games informs my reality, even if only to keep me tethered to it.

Writing this book about a tiny fragment of the video game universe has shown me, without a doubt, that video games are important, that video games are a reciprocal medium that changes us just as they ask us to change them, that games are, in fact, real.

So, why when things get small do I get interested? Because close examination of the small things forces a close examination of myself. Call it ego. Call it self-discovery. Call it…yeah, ego is probably right.

Share in the comments, what video game has made you contemplate your own life in an unexpected way?

Footnotes

| ↑1 | Though a bit of research suggests that the publication I heard about all those years ago, in college, so at least before 2006, could not have been Boss Fight Books. Oh well, I still champion BFB for, if not planting the seed, at least cultivating it. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | I like reading developer stories, but, well, I’m shy and awkward so interviewing people is something I don’t look forward to…but, for my What Remains of Edith Finch book I did it anyway, a little bit. |

| ↑3 | And for anyone who has played What Remains of Edith Finch, you can perhaps now understand why I was so drawn to the game’s themes of subjectivity. |