Why Can’t I Ever be the Bad Guy in a Video Game?

When I play a game that allows narrative choices, I always default to the white knight role, the honorable do-gooder, the kind of guy who kills only with kindness, the kind of guy who stands up for those who cannot stand up for themselves–paraplegics mostly–the kind of guy who saves damsels and his pennies, then donates those pennies to progressive causes that fight to eliminate the damselfication of women.

And when all that do-gooding is done goodly, and the credits have rolled, I’ll sometimes go back and re-play the game using a set of forced limitations as part of, what I call, an Asshole Run. This is a playthrough of the game in which I make non-white knight choices. I choose not necessarily the wrong choices, but for sure the choices that are most objectively the meanest. And to this day, I’ve never actually completed a full Asshole Run of any game.

Is being mean simply not fun? Are video games bad when played through a bad-guy lens?

I’m not going to pretend that all of you wrestle with the same morality that I do. Some of you may find it equally as easy to play the bad guy as the good guy, and so this post isn’t a comment on your moral imperatives as a person. You ARE a bad person. No further comment necessary. Just kidding. In fact, I’ll talk a bit later about a paper I recently read that offers the idea of Moral Management and moral disengagement which helps explain why you can be bad in a game but good in real life. And we all love academic papers. So, look forward to that!

But first, I’ve got to acknowledge what many of you are probably thinking: “Not all narrative choices in video games are so black and white, bad vs. good. Choices often have both positive and negative consequences.” While that’s absolutely true, I’ve found that in MOST games there’s still a narrative push toward the “good” ending, and signposts along the way often point in that direction. Take Fallout 3, for example, and the choice between blowing up Megaton and its citizens, resulting in a much better life in terms of wealth and living conditions for you, or saving Megaton which nets you a much smaller monetary reward and a paltry shack to live in, but you didn’t, you know, murder a ton of people.

Assuming you, the player, have come into Fallout 3 with a sound moral compass Fallout 3 reinforces that moral compass by first presenting you with the plight of the Megaton citizens. Megaton is, despite its drab appearance, a utopia of sorts. Its citizens—a mix of well-meaning ghouls, genuinely helpful law enforcement, and a chatty bar owner—are all generally respectful of one another, and are even mostly respectful of the cult members who worship an active atomic bomb located in the center of the town. Most players will experience—and importantly develop a sense of affection for—these friendly citizens BEFORE meeting the outcast character who seeds the temptation to eventually blow up the entire town for riches. The player is primed to think of Megaton as a good place, as a place worth protecting. You can choose to kill a bunch of people for wealth, but the game clearly doesn’t want you to do that. The player can make any choice, and both have positives and negatives, but it’s clear the game encourages you to make a specific choice.

There’s a larger consideration here, though, when it comes to a wide range of narrative choices. Game developers must, at some level, define what they want the player to do and therefore the choices available to them. Even games without binary choices, truly open-world, sandbox games that purport to allow the player freedom of choice and action, those games are still limited by the universal gaming constraint that if a game isn’t programmed to allow you to do something, then you can’t do that thing. Human beings cannot comprehend infinity, so there’s no way a human being will be able to program infinite choices and the infinite conclusions implied by them [1]except with self-learning AI, yes, you are correct Pedantic Joe, but self-learning AI is seeding by a human, and currently there are debates about the ethics of AI, which further proves my point).

Narrative-driven sandbox games generally have an ending, and because of this gamers assume, even if subconsciously, that their play decisions during gameplay are in service to that end. This implies a right and wrong choice at every step, or better yet a correct and incorrect choice at every step. Every choice is in service to an eventual end. In the case of multiple endings, marketing materials and fan communities often speak of the “good” ending, which isn’t always reflective of the moral good, but in most cases it is. Players strive to save all characters in Until Dawn. Killing Taro Namatame or failing to find the true killer in Persona 4 initiates the bad ending. In The Witcher 3, players are encouraged to push Ciri to make her own decisions, to respect her own desires, in order to get a good ending. Otherwise, Ciri dies. Cue the bad ending.

This is true, though less restrictive, even with MMORPGs. The goals of those games often aren’t necessarily about a single, final ending, and are more focused on shorter gameplay loops with more flexible states, but even with those the ethical binary is there, I believe, under the surface, constantly telling us that our character, our party, or even the game itself has a right choice among several wrong choices. Consider this: in an RPG when a decision prompt appears for you to make one of several narrative choices, do you read all of the options and make a choice, or do you push any button randomly. If you read the choices, you’re already mining the game for clues as to what the correct choice is for your character and situation, and the correct choice is often the one that keeps you on the path of the morally good conclusion or at least grants you access to tools and abilities to push you further on that path.

Even when games offer multiple paths and multiple endings, they aren’t ever really limitless. Game publishers will sometimes market their sandbox games with hyperbolic promises. Minecraft has used the phrase “limitless possibilities,” for example. And we, as consumers, are okay with that because we understand that those claims come with the implied caveat that, but, really they’re not limitless. It’s understood that our actions and choices will be limited to what the developers have allowed and the end states that the developers want.

It’s interesting that consumers allow this type of hyperbolic marketing. I don’t see it with other products. A jar of peanuts literally has to state that it contains peanuts. I understand that food allergies are much more serious than a player’s frustration with lack of actual, total freedom, but still the flexibility we allow with video game marketing is kinda crazy. And I’m not even talking about the use of mid-production vertical slices as marketing materials. “Fake” scripted game demos can be important, as they help focus a development team, a group of individuals with different aesthetic sensibilities, on a shared vision. But they shouldn’t be used as marketing materials.

The point here is that games have fundamental limitations in terms of scope, and because of that developers must make choices about how to keep a player interested and engaged. Tapping into a moral goodness is one way of doing that.

Now, I have to acknowledge that I know not everyone believes in a universal morality, that humans may not be hardwired toward ethical behavior. It’s a classic nature vs. nurture argument. Are humans inherently good or is our goodness entirely a product of our environment? I’m not smart enough to answer that question, so I’m operating under the belief that humans tend toward goodness in most situations. But if that’s where my thoughts ended, this post would have been over a long time ago: humans are good. Doing bad stuff is hard. The end.

But it’s not that easy. Not only are there plenty of bad people in the world, but stuff that would be considered evil in most situations in real life is easily rationalized in video games. Killing human proxies in video games is basically the point of most video games.

This brings me to that paper I mentioned earlier. The paper, titled “Moral Choice in Video Games: An Exploratory Study,” is about the idea of moral management, which is the idea that disengagement cues are embedded in the game narrative which play off the player’s desire to reach the end state. In other words, the game’s ending, and the player’s drive to see that ending, supersedes all else. Any moral alignment that the player brings to the game is effectively ignored during the play session as long as the game’s mechanics, narrative, and motivations align. This is the true essence of an RPG, one in which the player fully abandons their own morals to truly play a role.

There are problems with this, of course. The paper references other scholars who insist that in order for the game to even present a situation that allows moral management, the game must assume the players are coming to the game with some sort of moral alignment to begin with. But assuming moral management is at play, are we any closer to understanding why I have a hard time being an asshole in games? If moral disengagement is a thing, why am I immune to its effects?

Actually, I’m not immune to the effects of moral disengagement. Using Fallout 3 as the example again, I kill plenty of ghouls and raiders and super mutants and feel fine with it. That’s moral disengagement at play. Killing those things is in service to an end state. If blowing up Megaton and its citizens was the only way to finish the game, I would happily do so.

So, I suppose the real question is, if an end state is guaranteed, why do I feel compelled to make morally good choices to get there? Maybe it’s as simple as “doing good makes me feel good” and I like feeling good. I didn’t need an entire blog post for that conclusion.

There are still some interesting situations worth exploring, though. I find that when I play games with friends, the Asshole Run is easier. Is this because there’s an audience that I feel like I’m performing for? I’m turning the game into more of a spectacle than a journey? The idea of deindividuation may be at play here. This is the idea that in group settings I’m subject to the group’s morality more than my own. I talk more about deindividuation in my blog post titled “Why Are Some Online Gamers So Mean?”

The Asshole Run can also be difficult because often the game itself obscures which path is the most assholish. The game doesn’t generally show me the results of an alternate choice, so I’m left wondering what could have been. This is especially problematic when both choices seem equally moral and amoral.

Then there are games like the first Life is Strange in which the character herself second-guesses all of your choices. That’s just mean.

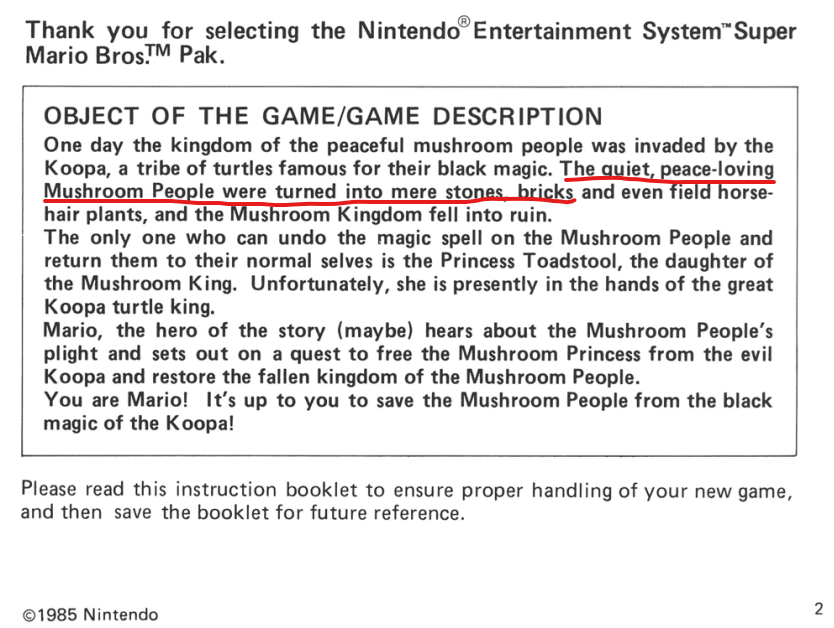

Also, what if the game itself doesn’t present the moral dilemma overtly? Take Super Mario Bros, on the NES, for example. That’s just a game about traveling through the Mushroom kingdom, breaking bricks to rescue a princess from an evil dinosaur monster. Seems morally straightforward, right? But consider the fact that those bricks you are breaking are actually imprisoned Mushroom Kingdom citizens. Really. This is canon:

This means you are ostensibly murdering thousands of innocents on your journey to rescue one princess. All the coins and power-ups that spew from broken bricks is moral disengagement at play. How can it be bad when the game encourages me to do it?

So, to the question of why do I have such a hard time completing an Asshole Run, the answer is probably pretty straightforward. I’m a morally good person playing games that generally encourage morally good behavior. So what can games do to make me act otherwise? They can offer paths that make moral disengagement easy, but I’m not confident such a path is sustainable. I don’t know of any successful game that actively encourages 100% amoral behavior for its entire narrative? Can you think of any? List them in the comments below.

Mentioned

Music credits

- Bossa Antigua by Kevin MacLeod, Link: https://incompetech.filmmusic.io/song/3454-bossa-antigua, License: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

- Pump by Kevin MacLeod, Link: https://incompetech.filmmusic.io/song/4252-pump, License: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Footnotes

| ↑1 | except with self-learning AI, yes, you are correct Pedantic Joe, but self-learning AI is seeding by a human, and currently there are debates about the ethics of AI, which further proves my point) |

|---|