Can you talk about a single book for one hour every week? Ministers/Priests/Pastors/Reverends/Etc. do. Why shouldn’t more books get the attention that religion texts do?

Okay, most books don’t have a centuries-long history, a following (even a lukewarm one), or a cultivated lifestyle (excluding the Twilights and Harry Potters). What most books do have in common with religion texts is an industry infrastructure built to support their messages and the text itself; compelling narrative for the ultimate goal of better understand the human condition.

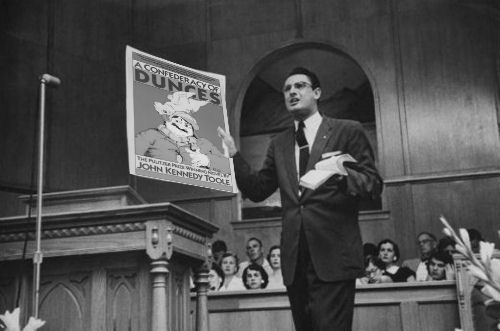

But week after week after week…how? Religious clergy have the amazing ability to use a single book as a point of reflection for EVERYTHING, from contemporary world events to domestic irritants. Natural disaster? War? Impoverished country? Acne? Grab a Bible, right? Why not grab The Confederacy of Dunces or House of Leaves? Each has interesting characters. Each depends on the reader’s own moral scope for impact. Each is a reflection of a life possibility, a Theory of Mind playground. Theory of Mind “…it is a term used by cognitive psychologists…to describe our ability to explain people’s behavior in terms of their thoughts, feelings, beliefs, and desires” (Lisa Zunshine, Why We Read Fiction, pg 15).

Basically, Theory of Mind means that by reading about fictional characters in books, whether Johnny Truant, Ignatius J. Reilly, or Job, we implicate ourselves in their positions. This is the heart and magic of narrative. Sure, religion texts have the benefit of worldwide reach and passionate (sometimes vehemently so) devotees, but those aspects alone don’t reserve for the books a singular position as the only texts worth preaching.

So claim a street corner and tell everyone why Ignatius J. Reilly is so repugnant yet simultaneously endearing.

Comments

3 responses to “Treat every book like The Bible”

But…you know, they aren’t talking about the Bible as ‘fictional reference point’, you know? The aren’t talking about it as even ‘a book’ like I might talk about The Man Who Was Thursday. Understand, I don’t disagree, not at all, with the general truth in what you’re saying, but (following your generalization) pastors, priests etc. they aren’t, say as you reference Job, unpacking what they believe is a nicely rendered fiction representative of some individual writer’s point of view and then giving their opinion, they are philosophically and religiously interacting with what they consider (this is further generalizing, but we both are and not in a harmful way) the revealed word of God, they come at the text with the imbued understanding that there is sublime meaning in the truths they are referencing by interfacing with it–it is more akin to reading from a history book, you know? Speaking about the events of American Society or historical advancements in medical philosophy or linguistic cognition (still just for example) and how they have implications that tangibly, literally touch on the world—priests, pastors etc. they aren’t ‘talking about a book’ in the same sense as one would be if talking about House of Leaves or Ulysses or The Tenant. As I say, I don’t disagree with the fact that there is endlessness to unpack from literature and non-literature alike—and I think people should focus, with literature, more on the fact that in speaking about it they are actually unpacking themselves, using the text as vehicle, not uncovering truth revealed in the pages but using the literature as reference for self exploration and self expression– I just wonder a bit about the overall slant, here. And I like to needle you, you know?

You are absolutely right. There is a level of conviction among many religious people that general readers with general texts simply cannot match. The history book comparison is apt. But I have trouble accepting that The Bible, for example, is universally taken as a 100% factual text, even among the devout. Bible stories are often referred to “Bible stories.” And the characters as “characters” even within certain churches. The terminology overlaps among the “true” and the “untrue” so I have to believe that somewhere, even if subconsciously (which is the -consciously that matters much of the times) Theory of Mind is right in that the human brain doesn’t differentiate between characters in novels and assumed historical figures. They are all personas, removed enough from ourselves as to be representations capable of reflection.

Ha! Reading this has reminded me of some of my “favorite” memories from past Lit courses. I’m pretty sure with all the different literary criticisms we’ve got access to, anyone could discuss the crap out of any book for an uncertain length of time. Unfortunately, I haven’t tested this beyond 12 week increments.