Are Video Games Good at Comedy?

Are video games good at comedy yet?

More precisely, are video games good at comedy in their own right. Of course video games can make us laugh. Steam has an entire category dedicated to funny video games. But most video games that make us laugh do so in ways that other mediums can also. The writing in video games, or the situational articulation of characters and scenes, these things make us laugh when we watch TV, when we read a book, and so of course they’d offer the same with video games. Nobody is going to argue that the Trashopedia entries in Donut County aren’t worthy of their own mock Mitch Hedberg album. They are. I’ve never laughed so hard when playing a video game.

But the humor with Donut County’s Trashopedia and Undertale’s incessant puns and Psychonaut’s slapstick gags is humor that’s possible across many different mediums. I want to know if video games have truly carved out their own methods of humor.

First, let’s start by defining humor and therefore giving us a way we can objectively measure whether or not something is funny, or at least as much as we can given the subjectivity of humor. My favored theory of humor, the Benign Violation theory, itself allows for subjectivity. So, there’s no getting away from the fact that what makes me laugh might not make you laugh, but the Benign Violation theory at least helps us categorize things as funny or not, even if the result of that humor isn’t an outburst of laughter.

So, the benign violation theory basically states that something is funny when

- it violates some norm or expectation

- does so without hurting anyone, and

- both the perception of the violation and of the non-threatening nature of the violation happen simultaneously

When it comes to humor by way of writing, the text sets up the expectations and then violates it with a punchline. Or take this poop-shaped coffee mug, for example:

The coffee mug is generally a banal part of your morning routine. The poop-shape violates this norm. And nobody has been killed. Even if you find this particular joke in bad taste, it’s still easy to understand why it’s funny.

Video games are unique. We’re connected to a video game by an input device, one that maps our thoughts to the actions we see. As we press buttons the feedback changes our approach, our input changes, and the loop continues until we arrive at a win state. No other entertainment medium offers this level of malleability. No other medium wants us to stretch and shape the product to an end while the product stretches and shapes us to that same end. This reciprocal molding is what makes video games uniquely immersive. And this contract between game and player relies heavily on a firm understanding of the ruleset. Most games literally tutorialize to the player. Books don’t tell you how to read. Movies don’t tell you how to watch. Video games tell you how to play. And this simple fact, I think, is why video games have trouble being humorous in their own right.

When I press up on the d-pad, I expect the player character to move up. When I press the R2 button, I expect the gun to fire. If that doesn’t happen, and I get shot instead, I don’t laugh about it. Why? The act certainly violates the expectation. But, in the context of the game, it does hurt someone. Me. My progress as the player, the reason I’m playing the game, has ended. Success depends on the game itself following the rules it’s requiring me, as the player, to follow.

So how do you benignly violate expectations with a video game?

The most straightforward example I can think of is during the intro tutorial of Portal 2. A robot chauffeur named Wheatley greets you as you wake from a long stasis. Testing for resulting brain damage, Wheatley gives you a simple command. You just need to speak. The game primes you for relief. If you honor the instructions, you’ll discover that your player character is not brain damaged, as was expected, and in fact can follow instructions perfectly, therefore subverting those expectations. However, this happens…

The punchline is a clever subversion of expectations, even when those expectations already seem to be subverted. This degree of layering and subverting expectations is difficult in any medium, but really shines in this video game example.

This subversion of the expected control scheme is, as I see it, the primary way video games currently use their unique offerings for comedy. A common flavor of this approach are games that make lack of control a primary feature. Gangbeasts, Octodad, and Human Fall Flat are all examples of this. Limbs are controlled independently, and forward momentum carries the character far beyond what game players have come to expect with most games. These games provide humor by defying the player to play them well. It’s not surprising then that these games are generally pretty forgiving with their lose conditions. If I am punished for the lack of control, then the violation is no longer benign.

Similar to the ragdoll approach of those games, the recent trend of simulator games manage to use a game’s intrinsic qualities for humor. Goat simulator, for example, promises to allow the player to simulate the life of a goat, which is mundane, and is humorous simply by nature of that juxtaposition. I expect a game to give me interesting experiences. Chewing cud in a petting zoo is not interesting. Therefore, benign violation. However, like Portal, Goat Simulator then subverts that expectation by encouraging the player to do things that are decidedly not goat-like.

Surgeon Simulator takes the opposite approach by suggesting that the game will let you experience something that requires immense skill. Then it subverts that expectation by limiting the player’s control to absurd levels. That a surgeon cannot control his own fingers is the humor.

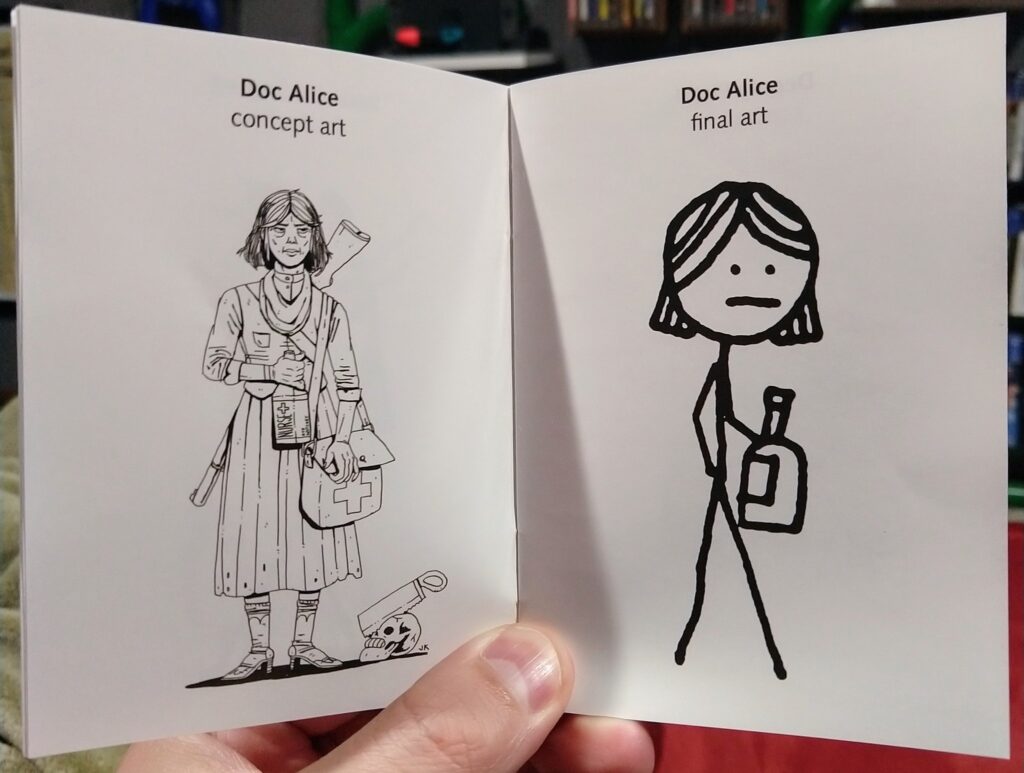

West of Loathing is an interesting example of video games doing comedy. While most of its comedy is applicable to other genres, one very unique way the game subverts expectations is with its art book. Video games sometimes come packaged with booklets full of concept art for the game with the expectations being that the reader will be guided in a visual chronology from sketch to concept to final rendering. But West of Loathing is a game with a stick figure motif, so the art book instead reduces the fidelity of the art over time rather than increasing it.

When will video games consistently use their own intrinsic properties for comedy? Will it ever happen often enough that awards are given at big award shows for video games that do comedy right? Will class be taught at universities about comedy in video games?